Sandrine Dudoit

A certain “je ne sais quoi”: An interview with Sandrine Dudoit

Sandrine Dudoit is a professor of Statistics and Biostatistics at UC Berkeley and current chair of the Department of Statistics. She earned her PhD in statistics from UC Berkeley in 1999 and joined the faculty in 2001. Her research focuses on statistical methodology and computing with applications to biomedical and genomics research. Sandrine is a beloved member of the department, not just for her high quality research and teaching, but also because of her dedication to creating a warm and welcoming community for all. When asked to describe Sandrine, students describe her as “amazing,” “someone who really cares about everyone in the department,” and someone whose “commitment to diversity and equity is inspiring.” In this interview, Sandrine tells us about her path into statistics and why she has long loved Berkeley.

Amanda Glazer (AG): How did you first get interested in math and statistics? You got your undergraduate degree in math and then switched to statistics for your PhD, right?

Sandrine Dudoit (SD): That’s right. I have an undergrad and a masters degree in math, more like probability theory, and then switched to statistics for my PhD. But it was never really a planned career in the mathematical sciences. It sort of happened randomly based on people that I met. Back in high school I was really all over the place. I was ok with math, but I wasn’t really that much into it. I think what really happened was I went to high school in France, and when you’re a good student they put you automatically on the math track.

AG: Do you get to choose your track?

SD: You get to choose, but there’s a lot of expectations. You’re not forced to do it, but you’re young, and your teachers go, “oh you’re a good student you should really do math / physics.” In my days, they used to call it “la voie royale,” the “royal path,” because it opened the doors to the best schools and the most prestigious careers. So, I ended up doing that, and it was ok with me because I kind of liked everything. And then my family moved to Canada.

AG: You were in Canada before France too?

SD: Yes, I grew up in both. I was born in Montreal to French parents. My family moved to France when I was a teenager, and then back to Canada right after I graduated from high school. So, I did all my schooling in the French system. The typical path when you do math / physics in France is you go on to engineering school. That’s what I was geared to do, but then my family moved back to Canada, and I enrolled in an engineering school. And in Canada, like in the US, they’re “real” engineers. They’re not mathematicians like they are in France. So that was the biggest shock to arrive in Canada in aerospace engineering. I had no clue what it was. I had a drafting class; it was horrible. My first two weeks I just panicked. I could do math but not that. Luckily, I had a good staff advisor that realized, “ok, this is not good for her. Let’s put her in math and physics.” So, I ended up back in math and physics. I did a lot of physics as an undergrad. That was good.

A lot of my choices have been based on people I really got along with and that mentored me. This one mentor told me, “well you should probably try statistics. It’s more applied.” So, I took a summer class in statistics, and I hated it. I think it was the worst class I had in my whole career. Statistics tends to be taught really poorly. It was taught by rote: here’s this catalogue of tests in a vacuum. So, I absolutely hated it and thought, “I’m not doing that ever again.” So, I went back to do math and then probability theory. Then again, through another teacher, I started doing more statistics and I thought, “actually this is kind of nice.”

It was a probability theory and a stats teacher that encouraged me to apply to grad school and to Berkeley. I really doubted myself, but they said, “No, no, you should really try it. What’s the worst that can happen? Just go for it. Apply to all these places in the US.” I was at an average university in Canada, but they said, “No, the worst that can happen is they won’t take you but just give it a shot.” They really supported me.

When I arrived at Berkeley, I had two things in mind. I was either going to do probability theory (I had been talking to Steve Evans), or something more with genetics because in the back of my head I had always thought genetics was so cool. So, I took 205 (Probability Theory) and 215 (Applied Statistics). I took 215 from David Freedman. That’s really what taught me statistics. Statistics is more than just a form of math. It’s a way of thinking, a way of reasoning about data. It was probably the hardest class I’ve ever taken, but unlike the other classes it stuck with me. The other classes were methods, and methods disappear. You forget about them. But 215 was about the philosophy of statistics and how to approach problems.

AG: Why did you decide to apply to primarily American grad schools?

SD: I studied at Carleton University in Ottawa. At that point, I’d met my ex-husband. We were both planning on going to grad school together. For him, France would not have worked at all. He didn’t know French, and it’s really hard to go study in France when you’re a foreigner. By that time I felt comfortable with living in the US or Canada. We made the choices of grad schools together. I already had a bias towards the West Coast. In the end, I had narrowed down the places I wanted to study at to UBC, Stanford and Berkeley. I lived in Davis actually the first four years of my PhD, because my ex-husband was a student at Davis and he was doing lab work, which made commuting more difficult for him.

AG: What do your parents do?

SD: My dad is a retired diplomat. He studied political science and law. My mom is a stay-at-home mom, but she studied political science, that’s how she met my dad.

AG: So, I’m assuming you moved because of your dad being a diplomat?

SD: Yeah, that’s right. My dad was a public servant, but he started moving only when I was a teenager. So, I only went on one posting with them, because I was living on my own after that. But I got to spend vacations in these cool places, like Madrid and Prague.

AG: Then you stayed in the bay area after your PhD?

SD: Oh yeah, I fell in love with the Bay Area right away. My first visit, which was in April or March before my first year, I thought, “wow I want to live here.” It’s funny, because before coming to Berkeley, on paper and based on what my mentors were telling me, I was leaning towards Stanford. I went to visit Stanford first and I loved it. I had a great time. So, I was pretty sure I’d go to Stanford. Then I spent two days in Berkeley and I was like, “ah this feels better.” Berkeley always felt like more of a fit for me. I always tell applicants that it’s really important to visit the departments they apply to: See how you feel, project yourself into a place, because it can be good on paper but it’s really how you feel in the environment and how you interact with the people that matters. Every time throughout my career I’ve always gone back to Berkeley. When I had job offers after my postdoc, again I had to make the choice between Berkeley and Stanford, and it just felt right in Berkeley. I was lucky that the timing worked to be able to get a job at Berkeley.

AG: Did you ever think about not going into academia?

SD: Oh definitely! It was never part of my plans. Well, even math was not in the plans at all. When I went to undergrad, actually I was not happy at all to be back in Canada. I wanted to stay in France.

AG: Why didn’t you stay in France?

SD: My parents didn’t want me to. They just thought I was too young and didn’t want a 17-year-old to be by herself in a big city like Paris. So, I was not happy at all to leave France. I would have liked to have studied political science or engineering in France. But instead, I was back in Canada and the default was that I’d just do engineering school. So, that was already not a planned thing. When I started my undergrad studies, I didn’t even know about grad school. I was completely ignorant. Really, really, like no career plan at all. It was only maybe in my fourth year of undergrad that I was like, “I’m actually enjoying it so sure let’s try two more years.” I also felt that it might be a bit too early to get a job because I didn’t know what kind of job I would want, especially with an undergrad in math; at that time I hadn’t done statistics. I liked studying math, so I thought, “let’s keep doing that.” Then in the second year of my masters, I still hadn't settled on a career plan. Again, I was fortunate to have really good mentors that believed in me and pushed me, because on my own I was just very, very ignorant about careers.

AG: It’s amazing the role and influence mentors have in people’s lives.

SD: Yeah, definitely. Without them, I wouldn’t have thought of applying to grad school. I didn’t have a direction.

During the PhD, again I wasn’t sure if I would stay with statistics or with academia. I also had a bit of a rough time as a postdoc. My PhD was motivated by a genetics question but it was very theoretical. It was like Markov chains on graphs, no data. It was fun but still very far from data. Then for my postdoc I thought let’s do some real applied work. So, I did a 180 and I did my postdoc in a biochemistry lab. I didn’t do the wet lab part, but I was where the data were being generated. It was the early days of DNA microarrays. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Pat Brown? He’s known right now as the person who created the Impossible Burger. That was my postdoc mentor. So again, I was lucky with who influenced me. I was very lucky to meet him. He had developed this new...have you heard about microarrays? That was about 25 years ago. It’s a high-throughput, biological assay that lets you measure the expression levels for entire genomes at once. Before, you had to do that one gene at a time, but Pat and a few others came up with this technology where you can efficiently scale up to an entire genome with thousands of genes at a time.

At the beginning, there was Pat’s technology which was all open-source. He had put out plans of how to build a microarray on a website. He claimed you could build it in your garage. There was also a version developed by a company that was all closed and proprietary. So, Pat already back then was all about open science. He gave a talk at Berkeley, at I-House, and I went to listen to his talk and I thought it was so cool: They’re generating tons and tons of data and there’s so many methods that need to be developed. There’s more data and more questions than we have the ability to answer. I thought that it’d be really cool to work with him. By that time, I was a little less shy, so I just walked up to talk to him and I said, “I would love to do a postdoc in your lab. I’m a statistician. I don’t know any biology.” But Pat thinks out of the box and takes chances and he said, “yes, let’s do it.” That was an amazing experience. It was a huge lab, so I was a bit lost at first having gone from our department where we’re pretty small to now a huge biology lab where I had to learn the language of biologists and the technical aspects of the experiments. I would go to group meetings and at first have no clue what they were talking about. But I learned so much from this experience and I feel it was an amazing preparation for the rest of my career in data science. Taking 215 with David Freedman and then being on my own working with biologists was “real” applied statistics. I would go in the lab and see how the data were generated, be involved in experimental design and have huge, messy datasets to analyze.

So, that was Pat that believed in me. Then I became much more applied and involved in software development. Towards the end of my postdoc, I met Robert Gentleman, who is one of the two original R authors (along with Ross Ihaka, a Berkeley Statistics graduate). At that time, Robert had already written R, and it had already become popular. Robert was getting involved in computational biology; I was aware that there was a great need for good statistical software in computational biology and that I had some serious learning to do in that area. Again, like statistics, I had taken programming courses as an undergrad, but the languages were taught in a vacuum and the focus was on syntax rather than general concepts. So, I felt very ignorant and insecure about computing. I started working with Robert, and, with a few others we cofounded the Bioconductor project, which is an open-source software project for biological data analysis. People say that when you play tennis against someone that’s better than you, you learn really fast. That’s how it felt with Robert and software; just being able to see how he was writing and developing software helped me a lot. So, that’s how I got into statistical computing. All about meeting the right people at the right time! I was lucky.

AG: And also following all of your different interests and not being afraid. That’s pretty cool.

SD: It was fun. I was lucky. I was still not sure if I wanted to go into academia when I was in my postdoc. I learned a ton, but it was also very, very stressful. Just realizing what it takes to be in academia and you know the lab environment. Pat was an amazing mentor, but it was a lot of pressure. Not by him at all but just the whole idea of academia about publishing and doing certain things. So, I’d considered going into industry or just doing something completely different. And then again, I thought, “what is there to lose? let’s apply for these jobs in academia.” There was an opening at Berkeley in biostat. They were looking for someone exactly in my area. That’s when computational biology was expanding and Berkeley wanted to have a bigger footprint.

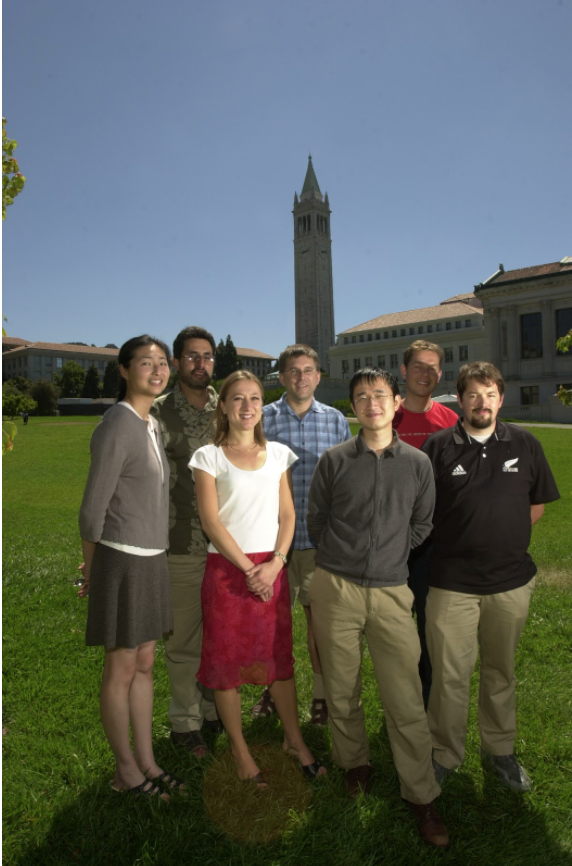

Project team in August 2003. Left

to right: Yee Hwa (Jean) Yang,

Rafael Irizarry, Sandrine Dudoit,

Robert Gentleman, Cheng Li,

Wolfgang Huber, and Ben

Bolstad.

AG: So, let’s talk a little bit more about Berkeley. What are your fond memories from the department or things you like best about the department?

SD: There’s so many of them. I think ultimately it’s the people that make the department. It’s a vague answer but that’s really how it is. You know, the atmosphere, the people. Of course, also, the level of the work and the quality of the intellectual environment. The department’s atmosphere is unlike what a lot of people thought, including myself, before coming to Berkeley. In my days Berkeley had this image of being really cutthroat. That you would be there and everybody would be competing against each other, but it was exactly the opposite of that when I arrived. I felt really supported. So, I think it was really the atmosphere of the department and a few key people that made me feel welcome: David Freedman, Terry Speed, Philip Stark, Deb Nolan, Steve Evans, and Nick Jewell.

AG: It’s really interesting how cultures form -- how we have our department that has such a good community but other departments that seem similar can have such different cultures.

SD: That’s right. I’m trying to put my finger on it but it's intangible. It’s just the feeling that is still there when we have events in 1011. It still feels very much the same as when I was a student. It probably goes back to before I arrived, to Betty Scott and people like that, that created a certain vibe.

AG: I think one thing that is really apparent to people, especially with you as Chair right now, is how much you care -- about the department and the people and everything. Where does that come from?

SD: Thank you. I do care a lot and I’m glad that it shows. I think some of it is probably because the department is sort of like a family. I feel a family connection with the department. I kind of grew up in the department. More than half of my life has been associated with the department. Those of us that were students in the department, like Peter Bickel and Bin Yu, we probably have this extra connection. We feel like the department gave a lot to us, and we want to give back and for the students to have the same experience as we’ve had. But it’s not just being a student at Berkeley. Deb, Philip, and Steve who came to the department as young faculty, also care so deeply. I guess it’s part of that intangible vibe. It feels like --

AG: Je ne sais quoi!

SD: Exactly! Je ne sais quoi! You want to give back and maintain this culture.

AG: Tell me about your current research.

SD: I love doing research and I wish I had more time to do research these days. A lot of my research is still genomics and high-throughput biological assays.

I’m still working with a collaborator from Berkeley that I started working with when I was a postdoc. His name is John Ngai, and he’s in MBC. And this guy’s just been amazing. He really appreciates working with statisticians, so we have this really good communication and we work together closely throughout a project. The ultimate goal is to understand the brain. This sounds super general and way too ambitious, but the way he and most biologists approach this is to divide and conquer. John is a neurobiologist and he uses the mouse olfactory system as his model system. The experiments he’s doing lately have been concerned with studying how stem cells differentiate in the olfactory system. He’s also interested in discovering novel cell types in the brain. The way he approaches that is using these single-cell high-throughput sequencing technologies. Nowadays, with these technologies, you can measure the expression levels of entire genomes at the resolution of single cells, as opposed to a collection of cells. With a collection of cells, you’d be measuring some sort of average, which is informative in some settings, like if you want to predict patient response to treatment. But if you want to classify cells or look at how a stem cell differentiates, you need to look at one cell at a time. So, that’s the technology he uses. These experiments are really good examples of data science workflows where you have complex data. These are very high-dimensional datasets, with 20,000 or 30,000 features. There’s a whole bunch of preprocessing steps. There’s sparsity issues. Often, preprocessing has a much larger effect than the choice of downstream machine learning method. So, we spend an awful lot of time early on “looking” at data, understanding where our data come from. You talk to biologists or a domain expert and they tell you, “oh here’s my question,” and you’re like, “ok, so what does this mean in statistical terms …” So, there’s also a lot of back-and-forth framing the domain question and translating it into something that’s a statistical or data enabled question. My methodological work falls in the area of high-dimensional statistics. Things like prediction, feature selection, cluster analysis. Upstream, there’s a lot of exploratory data analysis and visualization. It’s exciting because I get to play with really cool biological problems, like understanding how the brain works, and at the same time develop statistical methodology.

I really appreciate being a statistician, because there’s a lot of variety in our job. I happen to be working on biology today, but tomorrow I could say I want to work on something totally different. Of course, I’d have to learn the subject matter, but the methodology we develop is general, so studying the next domain you’re interested in and working in that is cool. My work has been a mix of theory, methodology, and computing. I don’t do much computing these days. I miss it. I used to love that back when I was a postdoc or young faculty. Now it’s more supervising students on computing projects. It would be nice to have more time for research. I’m lucky to have a great group and I miss seeing them in person.

June 2016. Left to right: Kelly Street, Davide

Risso, Jim Bullard, Sandrine Dudoit, and Kasper

Hansen.

AG: How have you seen things for women change, specifically in statistics and biostatistics?

SD: I think women are definitely more visible and more confident. That’s definitely a change that I’ve seen. In my cohort as a PhD student and as a postdoc, there were always quite a few women. I think it’s more the attitude of women but also the attitude of men with respect to women that has changed. That’s good to see. In the department itself, it’s nice that we have women in leadership positions. Deb’s been chair twice; she’s an associate dean now. Bin’s been chair once.

AG: Do you like being chair?

SD: Overall I do, because I feel it’s meaningful and because I care. But it’s been humbling and challenging. I could’ve done without the pandemic, but I care so I’m happy to do it.

A big challenge for me as a new chair is to move from what’s urgent and not so important to what’s important but not so urgent. I feel like I’m not doing very well on that tradeoff. Especially since the pandemic, I feel like I’m stuck in Zoom meetings all day and dealing with moving targets. I would love to be able to, and I need to work on that, step back and work more on big picture issues. The DEI action plan, the applied stats curriculum, hiring, the move into the Division of Computing, Data Science, and Society (CDSS): those are things I care deeply about and I would like to spend more time on. There’s so many exciting things to be done with our department. I like variety, so being chair is a nice change. I’ve been on the faculty since 2001, so almost 20 years. I like to learn. I like to be challenged.

~ Amanda Glazer